How do you organize your objects? In this article I will introduce a pattern for organizing so called noun-classes in your system in a untyped way and then expose typed views of your data using traits. This makes it possible to get the flexibility of an untyped language like JavaScript in a typed language like Java, with only a small sacrifice.

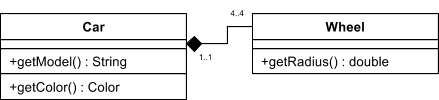

Every configuration the user does in your UI, every selection in a form need to be stored someplace accessible from your application. It needs to be stored in a format that can be operated on. The school-book example of this would be to define classes for every noun in your system, with getters and setters for the fields that they contain. The somewhat more serious way of doing the school-book model would be to define enterprise beans for every noun and process them using annotations. It might look something like this:

There are limitations to these static models. As your system evolves, you will need to add more fields, change the relations between components and maybe create additional implementations for different purposes. You know the story. Suddenly, static components for every noun isn’t as fun anymore. So then you start looking at other developers. How do they solve this? In untyped languages like JavaScript, you can get around this by using Maps. Information about a component can be stored as key-value pairs. If one subsystem need to store an additional field, it can do that, without defining the field beforehand.

var myCar = {model: "Tesla", color: "Black"};

myCar.price = 80000; // A new field is defined on-the-fly

It accelerates development, but at the same time comes with a great cost. You lose type-safety! The nightmare of every true Java developer. It is also more difficult to test and maintain as you have no structure for using the component. In a recent refactor we did at Speedment, we faced these issues of static versus dynamic design and came up with a solution called the Abstract Document Pattern.

Abstract Document Pattern

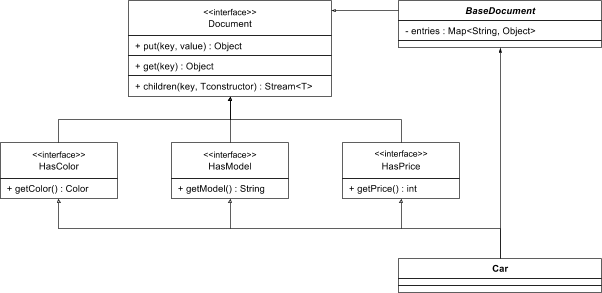

A Document in this model is similar to a Map in JavaScript. It contains a number of key-value pairs where the type of the value is unspecified. On top of this un-typed abstract document is a number of Traits, micro-classes that express a specific property of a class. The traits have typed methods for retrieving the specific value they represent. The noun classes are simply a union of different traits on top of an abstract base implementation of the original document interface. This can be done since a class can inherit from multiple interfaces.

Implementation

Let’s look at the source for some these components.

Document.java

public interface Document {

Object put(String key, Object value);

Object get(String key);

<T> Stream<T> children(

String key,

Function<Map<String, Object>, T> constructor

);

}

BaseDocument.java

public abstract class BaseDocument implements Document {

private final Map<String, Object> entries;

protected BaseDocument(Map<String, Object> entries) {

this.entries = requireNonNull(entries);

}

@Override

public final Object put(String key, Object value) {

return entries.put(key, value);

}

@Override

public final Object get(String key) {

return entries.get(key);

}

@Override

public final <T> Stream<T> children(

String key,

Function<Map<String, Object>, T> constructor) {

final List<Map<String, Object>> children =

(List<Map<String, Object>>) get(key);

return children == null

? Stream.empty()

: children.stream().map(constructor);

}

}

HasPrice.java

public interface HasPrice extends Document {

final String PRICE = "price";

default OptionalInt getPrice() {

// Use method get() inherited from Document

final Number num = (Number) get(PRICE);

return num == null

? OptionalInt.empty()

: OptionalInt.of(num.intValue());

}

}

Here we only expose the getter for price, but of course you could implement a setter in the same way. The values are always modifiable through the put()-method, but then you face the risk of setting a value to a different type than the getter expects.

Car.java

public final class Car extends BaseDocument

implements HasColor, HasModel, HasPrice {

public Car(Map<String, Object> entries) {

super(entries);

}

}

As you can see, the final noun class is minimal, but you can still access the color, model and price fields using typed getters. Adding a new value to a component is as easy as putting it into the map, but it is not exposed unless it is part of an interface. This model also works with hierarchical components. Let’s take a look at how a HasWheels-trait would look.

HasWheels.java

public interface HasWheels extends Document {

final String WHEELS = "wheels";

Stream<Wheel> wheels() {

return children(WHEELS, Wheel::new);

}

}

It is as easy as that! We take advantage of the fact that in Java 8 you can refer to the constructor of an object as a method reference. In this case, the constructor of the Wheel-class takes only one parameter, a Map<String, Object>. That means that we can refer to it as a Function<Map<String, Object>, Wheel>.

Conclusion

There are both advantages and of course disadvantages with this pattern. The document structure is easy to expand and build upon as your system grows. Different subsystems can expose different data through the trait-interfaces. The same map can be viewed as different types depending on which constructor was used to generate the view. Another advantage is that the whole object hierarchy exists in one single Map which means that it is easy to serialize and deserialize using existing libraries, for example Google’s gson tool. If you want the data to be immutable, you can simply wrap the inner map in an unmodifiableMap() in the constructor and the whole hierarchy will be secured.

One disadvantage is that it is less secure than a regular beans-structure. A component can be modified from multiple places through multiple interfaces which might make the code less testable. Therefore you should weigh the advantages against the disadvantages before implementing this pattern on a larger scale.

If you want to see a real-world example of the Abstract Document Pattern in action, take a look at the source code of the Speedment project where it manages all the metadata about the users’ databases.